Any week spent in one of Susan Khalje’s Couture Sewing School classes is a week filled with opportunity. This past class was my third one taken with Susan, and I have come to expect that I will learn unexpected things! My first class with her was the Classic French Jacket; the second class was when I started my color-blocked coat; and this class saw the beginning of a silk formal dress which I need for a black-tie event in early July.

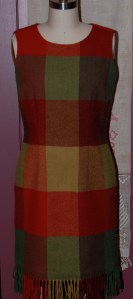

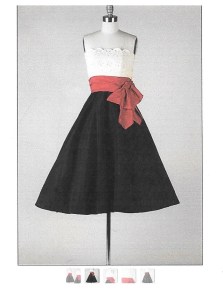

She asks her students to come with a prepared muslin (toile), ready for fitting. I have so many vintage patterns for long, lovely, fancy dresses, that it was difficult to focus on just one. As it turned out, I found myself drawn repeatedly to a dress which I had pinned to one of my Pinterest boards, and it is this dress which became my inspiration:

I say “inspiration” as I knew I wanted to make certain changes. I decided I did not want to go completely strapless. Instead I envisioned a strapless underbodice, covered by a lacy, semi-transparent, sleeveless overbodice, both in white. I had already purchased a silk-embroidered organza (from Waechter’s Fabrics, before they closed their business), and I had also already purchased 3½ yards of sapphire-blue silk taffeta from Britex Fabrics. Those were my fabrics of choice for this project.

I say “inspiration” as I knew I wanted to make certain changes. I decided I did not want to go completely strapless. Instead I envisioned a strapless underbodice, covered by a lacy, semi-transparent, sleeveless overbodice, both in white. I had already purchased a silk-embroidered organza (from Waechter’s Fabrics, before they closed their business), and I had also already purchased 3½ yards of sapphire-blue silk taffeta from Britex Fabrics. Those were my fabrics of choice for this project.

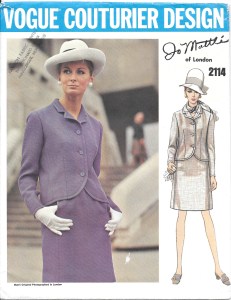

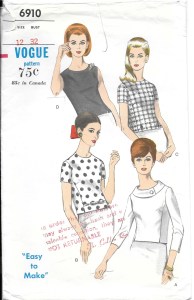

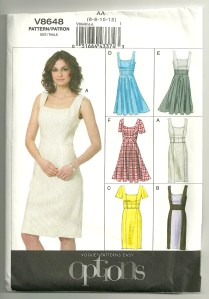

I started with the strapless top and the sleeveless top from this current Vogue pattern:

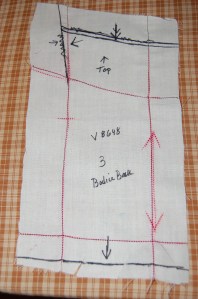

Here’s what happened when Susan fitted the muslin on me:

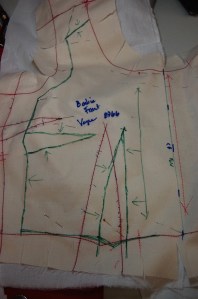

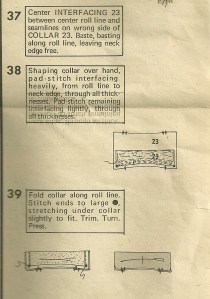

The pattern for the strapless under bodice consisted of a front panel, two side princess panels, and two back panels. However, Susan divided each side princess panel into two pieces, giving me 7 bodice pieces rather than 5.

. . . and here is the back. I made the back into a V-shape, which was a minor adjustment to the pattern I was using.

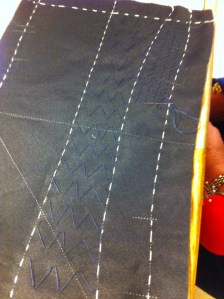

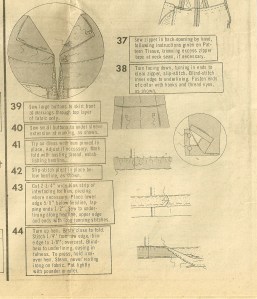

One of the reasons I wanted to start this dress under Susan’s tutelage was for the opportunity to learn how to add boning to a structured bodice. I knew the fashion fabric for the strapless underbodice would be white silk crepe de chine. What I did not know is that the channels for the boning would be cleverly made out of two pieces of silk organza, with parallel stitching strategically placed every couple of inches – making the perfect slots for the pieces of boning.

Then the shocker came: in order to keep the boning from showing through to the right side, I needed to add another layer of … something. When Susan suggested white flannel – flannel! – I was skeptical, but trusting (I think!). I kept thinking of the bulk that flannel was going to add to this very fitted underbodice, but Susan assured me it would work. She consoled me by telling me that we would be able to cut away the seam allowances of the flannel, reducing much of the added bulk. But the real surprise was the wonderful softness the flannel added to the finished underbodice. The flannel not only camouflages the boning on the right side, it also adds an amazing smoothness to the appearance of the underbodice.

Once the underbodice was complete, I set about to start the embroidered silk organza overbodice. We played around with the placement of the motifs, making sure that two big “daisies” would not be right on top of the bust.

And I wanted to see what the embroidered silk organza would look like over the strapless under bodice. So pretty!

Interior seams were finished by hand, and darts were left as is, with no additional finishing. The neck and armhole edges were another story, as they would need to be bound in bias-cut crepe de chine. I found this very tedious and time-consuming and appreciated Susan’s suggestions and tips to help make these delicate finished edges as even as possible. First I practiced, then I sewed, then I took out stitches and started over again, carefully clipping away noticeable bulk from the embroidery in that narrow edge.

Once both bodices were completed, I basted them together at the waist. The only other place they are joined is at the back seam where the zipper will be inserted.

It surprised me that no other joining of these two bodices would be needed, but once again, I have found that the unexpected often makes the most sense when it comes to couture sewing!