Sometimes extra incentive is needed to push through a project which turns out to be more difficult than anticipated. Such was the case with this pink silk jacquard dress.

I had purchased this fabric quite a few years ago online from Britex Fabrics. I knew it was a dressy fabric, and unsure of what form this dress would take, I made the decision to purchase four yards of this 58” wide silk. That gave me some latitude in my selection of pattern.

Finally last Spring I made a decision about what I wanted this dress to be. That was precipitated by the arrival of a beautiful invitation to a very special event this Fall, and of course (!) I needed a new dress to wear to it. The fabric is a dressy, shimmery silk jacquard, so by its very nature it would make up into a dress which had a certain glamour to it.

I decided to use a go-to pattern I have used a few times already and make a classic shirtdress. That may seem like a strange choice, but I envisioned it as very dressy and flowing, and quite appropriate for the fabric.

While this idea was percolating, I happened to attend a luncheon/presentation by a wonderful organization called the Ibu Movement. (Pronounced ebu, with a long “e,” this is an Indonesian word meaning “a woman of respect.”)

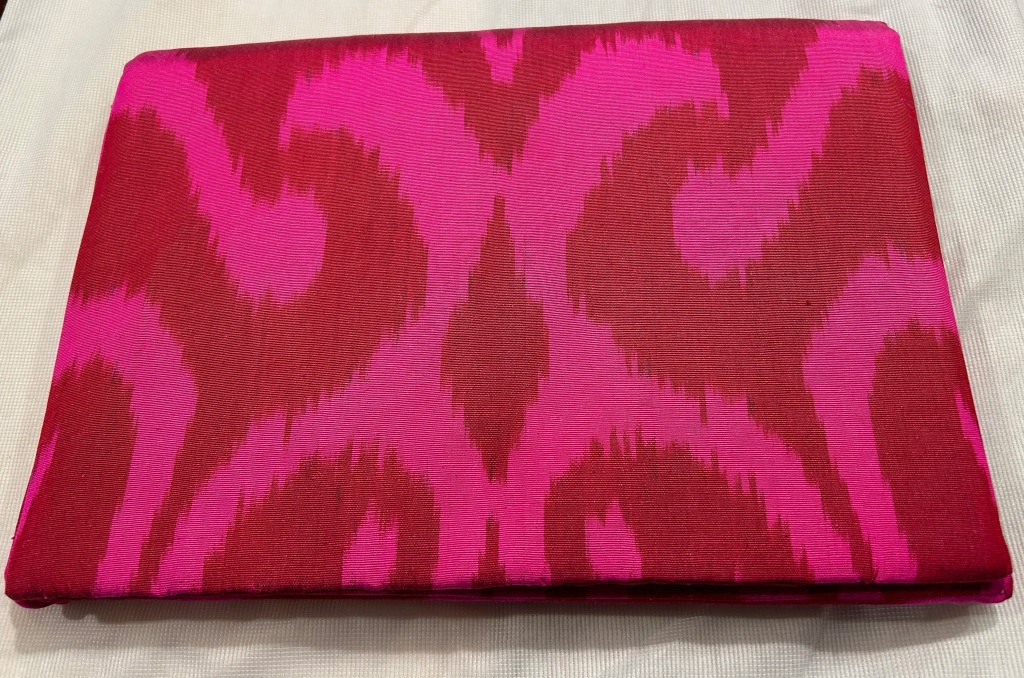

The pop-up shop accompanying this event was filled with gorgeous clothing, accessories, even shoes. When I saw this envelope clutch, I knew it would match my silk fabric perfectly and would be the perfect addition to my as-of-yet-to-be-sewn pink dress. Little did I know at that time it would be the catalyst to make sure I finished the dress!

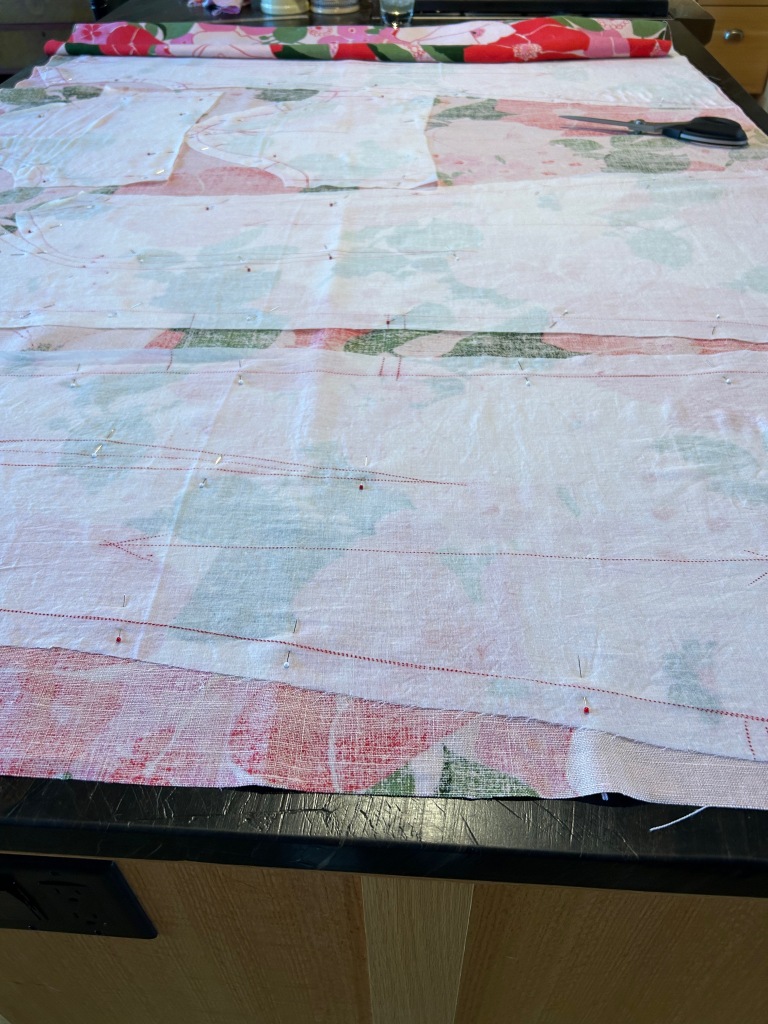

My first clue as to the fussiness of the fabric was as soon as I pressed it and laid it out for the placement of my muslin pattern. Here is what I noticed:

- The fabric had a slightly loose weave to it, making it almost stretchy, certainly very slinky. Keeping it properly aligned on the straight of grain was going to be a challenge.

- The fabric frayed easily.

- It also was prone to shedding silk fibers. I decided I needed to handle it as little as possible to mitigate this situation.

- The jacquard weave in it had a definite horizontal and vertical pattern to it, meaning I would have to match the design horizontally and vertically across seams. Although I am used to matching plaids and prints, this was a little different as the woven design was of irregular form.

I decided to underline the dress (except for the sleeves) with a very lightweight silk batiste, which I hoped would give it some substance, but still preserve the flowing nature of the fabric. I made the conscious decision not to add an additional lining to the dress.

Although I rarely use fusible interfacing, I realized very early on that sewn-in interfacing was going to shift around and cause all kinds of problems. Luckily, I had been introduced to a very finely woven, fusible German interfacing available from Farmhouse Fabrics. I had some on hand and found it to be the perfect stabilizing foundation for the cuffs, the front facing, the collar, the collar stand, and the hem.

So, that solved one big problem for me. I was still concerned about being able to get the hem even. I had good reason to be concerned! It took two tries to avoid having either a bubble appear or uneven dips around the perimeter.

The final quandary I had was the buttonholes. Because the fabric shed silk fibers so easily, I was really worried that my buttonhole attachment might grab onto those fibers and make a mess. I did some sample buttonholes, which confirmed my suspicions. So – I used wax paper between the foot of the attachment and the fabric, cutting little windows in the wax paper where the buttonholes would be sewn. It worked like a dream.

This was not a particularly fun dress to sew, but that “perfect” handbag kept me focused. And I am glad it did, as the dress was a success in the end. And it always feels like an accomplishment to use fabric which has been lying in wait for so long.

Completing the Pink Coat Ensemble

Although I hope to wear my pink wool coat (completed Spring of 2019) with various dresses and skirts, I particularly wanted to make a skirt which would coordinate with it. That way I would have a “planned” ensemble. I envisioned a petite pink-and-gray houndstooth wool, or a mini-checked pink-and-gray wool. After a wide search and coming up empty-handed, I was just about convinced I was not going to find either of those two fabrics, at least not in the time frame I planned. And then I found a lightweight wool and silk blend on the website of Farmhouse Fabrics. It was a variegated gray and oyster-white plaid with a pink pinstripe running through it on the cross-grain. Although it looked lovely on my computer screen, I wasn’t sure it would fit my needs, so I ordered a swatch. From the swatch I could see its beautiful quality – and its perfect colors – so my search was over.

I am so accustomed to using silk organza as my underlining, but the incredible softness and delicacy of this fabric made me think twice. I thought silk organza would undermine the fluidity of the wool/silk blend, so I decided to use a very lightweight cotton batiste instead. Using the Susan Khalje pattern for which I already had a toile (yay!), I made a very simple straight skirt. Just for fun I decided to line it in pink silk charmeuse. I had some in stock as I had used it for the pocket linings in my pink coat. I also lined the waistband, which I like to do when sewing with wool.

The pink charmeuse lining is my unseen homage to this color which I love so much.

I inserted a lapped zipper by hand in the center back seam.

I angled the center back vent toward the center back seam so that it will hang evenly when I am wearing the skirt.

It is easy to see the angle on the vent with this particular fabric.

One side of the vent folded back.

When I cut out the lining for the coat, I maneuvered the pattern pieces to give me a long narrow length of the silk, which I made into a scarf.

Paired with a V-neck gray sweater, it proves to be the perfect accessory. As Christian Dior said in The Little Dictionary of Fashion, “In many cases, a scarf gives a final touch to a dress.”

It’s a nice combination of colors!

The scarf is a pretty addition to the coat, I think.

It is rewarding to see my vision become reality!

So, now the big question, one which I have been asking myself frequently as of late, “When and where will I be wearing this lovely ensemble?” It seems life is just so despairingly casual now, affording few opportunities to wear pretty dresses and skirts and specialty coats. I try to buck the trend when I have the place and time to do so – and I have yet to feel like I have been overdressed. Of course, Christian Dior had something to say about this, too. “Generally it is very bad to be overdressed, but I think that in certain circumstances it is very impolite and wrong to be underdressed.” I could not agree more and personally prefer to be slightly overdressed than underdressed. How about you? I do hope my pink coat, paired with this gray skirt, will prove to be the perfect dressing for many occasions. I am certain I will enjoy wearing them.

48 Comments

Filed under Christian Dior, Coats, Fashion commentary, hand-sewn zippers, Linings, Scarves, Straight skirts, Uncategorized, underlinings

Tagged as Christian Dior, coats, couture construction, Farmhouse Fabrics, fashion sewing, scarves, Straight skirts